Professor Davis, Chair of the Family is Culture review – which found a “culture of non-compliance and a significant lack of accountability” in the NSW out-of-home care system in relation to Aboriginal families – says the review cannot be “left on a bench to gather dust”.

“Instead,” she says, “the Minister [of Families, Communities and Disability Services] should implement the recommendations as a matter of priority.”

“The Australian public and Aboriginal children and families are yet to be informed of the actions that will follow our independent review.

“This is despite it being seven months since the review was made public.”

The NSW Department of Communities and Justice issued a short statement with the release of the review in November 2019, where it stated that the department “will work through the report and prepare preliminary advice in the first half of 2020 on the suggested way forward”.

No preliminary advice, or a set date for the release of this advice, has been announced.

The review examined all cases of First Nations children in out-of-home care in NSW during 2015-16. Image: Family is Culture review, artwork by Charmaine Mumbulla.

“I hope that the recommendations are adopted in full and an announcement on the way forward is forthcoming,” Prof Davis says.

“Given the fact that coronavirus pandemic puts these families at more risk, the implementation of these recommendations should be accelerated to ensure support is available to families that are under further pressure.”

Any delay in action would be emblematic, Prof Davis says, of what the review uncovered: that of an active “outward appearance of compliance that shields a culture of non-compliance”.

“This ritualism present in the bureaucracy is hurting Aboriginal children and young people,” Prof Davis says, “and these families deserve better.”

“The review’s 125 recommendations show the way forward. [In the review] we don’t just point out the issues, we have laid out the path to achieving meaningful change.”

Unethical, poor practice: the review’s damning findings

The Family is Culture review examined all cases of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people in NSW out-of-home care between mid-2015 to mid-2016, representing 1144 children and young people entering care.

The review described an out-of-home care system that is “incomprehensible to outsiders”, and one which has “lost sight of the actual goal of protecting children in its day-to-day operation”.

The Davis review also found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are over-represented in out-of-home care, representing over “37.5 per cent of children entering care”, despite being 5 per cent of the population. This overrepresentation of Aboriginal children entering care has increased in proportion to 40 per cent despite overall numbers decreasing since 2015-16 according to the latest data (2018-19).

“We were concerned about many of our findings,” Prof Davis says.

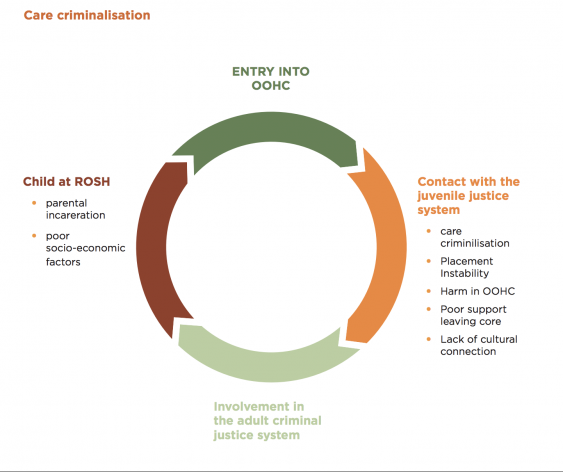

“Much of what we found is pertinent to issues brought into focus today: for instance, in our review, we show how Aboriginal people can be trapped by the justice system through ‘care criminalisation’.

The review explores the link between the over-representation of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care and the justice system through 'care criminalisation'. Image: Black Lives Matter protests in Australia.

“We also describe the link between the over-incarceration of Aboriginal people and involvement with the out-of-home care system. These issues don’t operate in isolation either, they’re connected an intergenerational story of trauma with Aboriginal child removals and oppression.”

The review reveals how early intervention and support opportunities for families are often “ignored” and highlights “unnecessarily traumatic removal practices” that often involve the police.

The damage of removal on children is significant and it should be “last resort” in all incidents, the review highlights, but in practice, this isn’t the reality.

In several cases, outlined in detail in the review, newborn babies are removed from the hospital straight after birth without notifying either parent. This occurs, in examples explored in the review, despite early child protection reports highlighting the need for early intervention and family support; yet no such early intervention is pursued before removal.

Professor Megan Davis, Chair of the Family is Culture review, was concerned by several findings.

The review noted there were “multiple instances of poor and unethical newborn removal practices”.

In many incidents, the child’s family and kin were also not consulted with regard to placement possibilities or removal.

Such cases include, as described in the review, family members calling and requesting to assume care of removed children, only to have these requests ignored or denied by caseworkers, without any subsequent documentation of reasoning behind those decisions.

“This is why we are explicit in our many recommendations: wide-ranging change is urgently needed in out-of-home care, as this system – as it currently operates – still has broad negative consequences for Aboriginal people, particularly through dislocating them from kin and culture.”

Calls to fix a system that fails Aboriginal families

In March this year, a letter to the Premier of NSW, issued by a collective of organisations – including NSW's Aboriginal child and family peak organisation, AbSec – called for all 125 recommendations of the review to implemented by the government.

Ahead of Sorry Day in May, AbSec reaffirmed this call and announced that the Department of Communities and Justice would be reducing its funding at the end of June. Sorry Day recognises the state-inflected trauma on the Stolen Generations through forced child removals.

Gareth Ward, the NSW Minister for Families and Community Services made a statement which said that funding is not being reduced, rather projects that were time-limited and that finish in June would have their funding ceased – though the department could not say which projects related to this funding cut when asked by the South Coast Register.

A letter from a coalition of organisations pushed for all 125 recommendations of the review to be implemented.

In regard to Family is Culture, the Minister and his department stated again that they were considering recommendations and will work on preliminary advice in the “first half of 2020”.

“This [funding cut] was another concerning step,” Prof Davis says, “as due to the little regulatory oversight in the [out-of-home care] system, AbSec plays an important role as an informal regulator.”

The role of Aboriginal organisations and activism as informal regulators was noted throughout the review, with the report itself being commissioned after a push from the Aboriginal ‘Grandmothers Against Removals’ grassroots advocacy group.

“It shows further that the department needs to address the findings of our review and its recommendations; this decision [regarding AbSec funding] stands in contrast to the need for self-determination – in the true sense – as outlined in Family is Culture review,” Prof Davis days.

Policy not being implemented and there is a severe lack of scrutiny

A key finding of the review centred on the wide-spread non-compliance with the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle (ACPP), despite an active effort to have a public appearance of compliance through “policies espousing a departmental commitment to ACPP, glossy brochures, [and] tick-a-box forms”.

The review found that 'ritualism' is a problem within the out-of-home care system. Image: Artwork by Charmaine Mumbulla, Family is Culture.

The ACPP, broadly attempts, wherever possible, to keep “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children connected to their family, community, culture and country; recognising community as a strength for children”.

The non-compliance to this vital principle has been compounded, the review finds, by the lack of accountability mechanisms and “a pervasive lack of transparency among key players in the ... oversight system, and lack of effective monitoring of [out-of-home care] providers”.

The decision to remove a child without a proper risk assessment applied or even recorded, the decision to not find family, the decision to not return the call of anxious, loving and willing Aboriginal family carers, the decision to allocate disempowered and struggling parents restoration goals of Sisyphean proportion; these and many more that we uncovered in our deep dive, have had an irreversible impact upon the Aboriginal child or young person.

– Family is Culture, review, Professor Megan Davis’ Introduction, p. XVII

One of the most significant recommendations, in light of these findings, is for “the NSW Government establish and appropriately resource a new independent statutory body” for child protection, and for there be at least one Aboriginal Commissioner and an Aboriginal Advisory body.

Care criminalisation and the cycle of incarceration

The link between out-of-home care and involvement in the criminal justice system is well known in Australia. The Family is Culture review cites the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC), which found almost half of the deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people examined by the commission had been “removed from their families”.

The Family is Culture review also raises the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s finding that “children and young people who were in OOHC were 16 times more likely than other children to be under youth justice supervision”.

Placement in out-of-home care, “exacerbates the existing risk that maltreated children will become involved in criminal offending”, largely through what the review terms as ‘care criminalisation’.

Care criminalisation can trap children in the justice system, Prof Davis says. Image: Supplied © Family Is Culture

Care criminalisation is a process “by which children and young people in OOHC are arrested for behaviour that would usually result in a disciplinary response from parents and not a criminal justice-related response from police officers”.

“For example,” Prof Davis says, “children may be arrested for offences that occur in their placements, such as damage to property.”

A significant issue raised in this context within the Davis review is the linkages between children at risk of involvement with the youth justice system and poor practice in risk assessment and subsequent placement instability.

During consultations, the review was informed that “cultural bias affected the way in which caseworkers approached the assessment of risk with Aboriginal families. For example, one stakeholder noted that ‘Aboriginal’ was often used as a stand-alone risk factor.”

For “almost half of the children who entered care”, the review identified practice issues in the way the children came into care.

Such cases include removing a child while the mother was out shopping, removing a young person while they attended their formal, and removals that occurred at “2am”.

If children are also subject to maltreatment in care, or placement instability, the risk of “crossing over” with the youth justice increases significantly, and consequently the risk of involvement with the adult criminal justice system is exacerbated.

There were several extremely concerning cases ... which raised serious questions about the harm of child removal and the safety and welfare of children in care. For example ... an Aboriginal child in care was described as having changed placement 16 times in less than two years, moving between residential care, juvenile justice detention, rehabilitation, and hotels rooms.

This child was also profoundly disconnected from culture and it was identified that no attempts were made to promote his cultural connections and family relationships while he was in care.

– Family is Culture review, p. 280

The Davis review also calls for reform of the Children’s Court after finding that “FACS present[ed] misleading information to the Children’s Court during care and protection proceedings [which] calls into question the court’s ability to adequately balance the relevant harms on the basis of the information provided to it”.

Intergenerational pain, historical continuity

The history of child protection in Australia is also explored by the review, not as a way to directly “assist in generating recommendations for modern system” but to place the views of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on child protection in its “historical context”.

This history begins, the review notes, at ‘First Contact’ at the time of European colonisation in 1788; where Aboriginal peoples were dispossessed and conflicts erupted with “the ‘Frontier Wars’ ”.

Image: Supplied, Family is Culture review.

This led to an era of so-called “protection”, whereby “passage of several statutory frameworks to regulate ‘protection’, including those establishing reserves and missions, aimed at the compulsory racial segregation of Aboriginal people from the wider community”.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

– Uluru Statement from the Heart

This sustained history of “oppression, paternalism and cruelty,” the review explains, includes “assimilation policies” which resulted in the Stolen Generations.

The review notes that the consequences of this “can still be seen today when, for example, parents are judged for their lack of engagement with FACS caseworkers without the slightest regard for the historical antecedents of Aboriginal peoples’ mistrust of the state”.

The review also explores the history of child protection and First Nations peoples including the stories of the Stolen Generations. Image: Stolen Generation children at the Kahlin Compound in Darwin, Northern Territory, 1921.

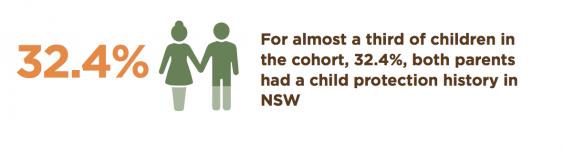

The intergenerational nature of child protection for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is seen throughout the review, to the extent that “key risk factor for a child being removed is previous experience in the child protection system or having family members or parents in the system”.

Over two-thirds of mothers of children in the cohort of the review had a child protection history in NSW (68.3 per cent), a quarter of mothers of children had previously been in an out-of-home care arrangement themselves as a child (25.5 per cent), and “almost a third of children in the cohort, 32.4 per cent, both parents had a child protection history in NSW”, the review finds.

“If child protection authorities keep removing children for symptoms of neglect, rather than treating the root causes of that neglect, then numbers in OOHC will keep increasing.”

When police are used for removal, especially riot police, this has historical continuity. When babies are removed at hospitals or a pre-natal risk notification is made because the mother is Aboriginal, this has historical continuity. When siblings or twins are separated in care, this has historical continuity.

When families reach out … for a carer assessment and are ignored and telephone calls go unreturned, this has historical continuity. When mums and dads are given unrealistic, unachievable goals in order to have their children or grandchildren restored to them, this has historical resonance.

Some of the restoration goals are incontrovertibly impossible to be achieved. Some of these practices demonstrate concrete examples of institutional racism. The system is replete with practice that renders our people voiceless and powerless.

– Family is Culture review, Professor Megan Davis’ Introduction, p. XVI

The findings of the report, Prof Davis says, tells of the structural nature of the issue. There was, she says, some incidents of good practice, yet a prevailing systemic cultural gap exists.

Coupled with a lack of transparency and accountability, “poor practice is allowed to flourish”.

“The right to self-determination is not about the state working with our people, in partnership,” Prof Davis writes in the review.

“[Instead self-determination] is about finding agreed ways that Aboriginal people and their communities can have control over their own lives and have a collective say in the future well being of their children and young people.

“As the Uluru Statement from the Heart implores:

“When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.”

Megan Davis is the Balnaves Chair of Constitutional Law, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Indigenous and Professor of Law, UNSW, and a proud Cobble Cobble woman from the Barrungam nation.

Prof Davis is the Chairperson of Family is Culture, an independent review of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care, commissioned by the Department of Communities and Justice in 2016 (then FACS) and released in November 2019.

Read more: Remove problems, not children